The Displaced Persons Camp (1945-1950)

After the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was liberated by the British Army on 15 April 1945, the survivors were taken to the nearby Wehrmacht barracks where they received medical treatment. The former concentration camp prisoners and forced labourers who had been deported to Germany from all over Europe were given the status of “displaced persons” (DPs) by the Allies. This status gave them the right to special assistance and care.

Most of the survivors returned to their countries of origin, but many – primarily Jewish and Polish former prisoners – remained in Bergen-Belsen.

These DPs were initially housed together on the orders of the British military government, but from June 1945 separate living areas were established for the two groups.

At times, there were up to 10,000 people living in the Polish DP camp at Bergen-Belsen, which was disbanded in September 1946. The Jewish DP camp held up to 12,000 people. This camp was closed in September 1950.

-

The Emergency Hospital

The Emergency Hospital

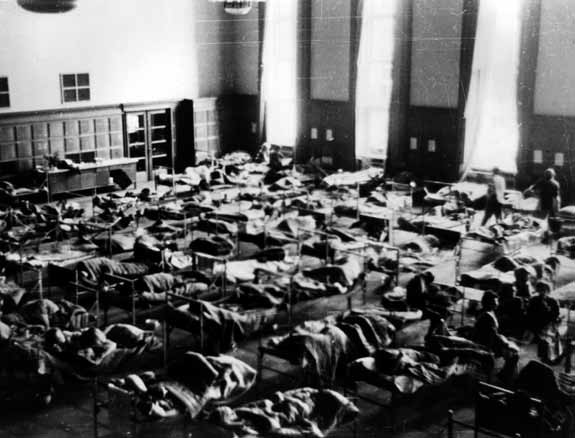

When British soldiers reached Bergen-Belsen, they were not prepared to deal with either the typhus and typhoid fever epidemics that were raging through the camp or the extreme malnourishment of the prisoners. Even as the troops buried thousands of bodies in mass graves and burned down the contaminated huts in the grounds of the former concentration camp, the British Army set up an emergency hospital in buildings at the nearby former Wehrmacht barracks. Over 11,000 ailing survivors had to be treated there as late as June 1945. Since the emergency hospital did not have the capacity to handle so many patients, a number of survivors were moved to hospitals and emergency sick bays in nearby cities like Celle.

Just one week after the liberation, several British Red Cross units and other civilian relief personnel arrived at Bergen-Belsen to assist the military. The British Red Cross took over responsibility for providing civilian medical care. The Red Cross staff consisted of doctors and aid workers from many countries, including numerous liberated prisoners. German doctors and nurses were also pressed into service by the British authorities.

As the number of patients decreased, the barracks buildings were turned into living quarters and the emergency hospital was transformed into the Bergen-Belsen DP camp.

-

The Polish DP Camp

The Polish DP Camp

In early September 1945, there were still over 10,000 gentile Poles living in the Bergen-Belsen DP camp. Prior to the liberation, they had been forced labourers, POWs or concentration camp prisoners. These DPs refused to go back to Poland because they opposed the communist regime that the Soviet Union had imposed in Warsaw. Though the government in Warsaw wanted to encourage the DPs to return quickly, the Polish Government-in-Exile in London warned the DPs against this.

Everyday life in the Polish DP camp was largely self-governed by a camp committee. A vibrant social, cultural and religious life developed. Nursery schools, schools and professional training courses were set up, and a daily Polish information bulletin was soon replaced by the DP camp’s own weekly paper. The cultural and athletic activities in the camp included choirs and orchestras, art exhibitions, a cabaret troupe, football teams and track-and-field competitions.

Nonetheless, the DPs’ memories of their persecution were ever present. The Polish camp committee established a department for documenting Nazi crimes, and in November 1945, during a Catholic Mass attended by thousands of DPs, it had a large wooden cross erected in the grounds of the former concentration camp.

In September 1946, the British military authorities dissolved the Polish DP camp at Bergen-Belsen and transferred its remaining inhabitants to other DP camps in the British Zone. Around two thirds of the Polish DPs in the British Zone returned to Poland, while the rest tried to emigrate primarily to the USA or Canada.

-

The Jewish DP Camp

The Jewish DP Camp

The Jewish DP camp was home to former prisoners of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp as well as thousands of other survivors of the Shoah from central and eastern Europe. For most of these Jewish DPs, remaining in Europe had become unthinkable. Very few of them had any relatives left, and their houses and property had either been stolen or destroyed.

Following democratic elections in September 1945, the Jewish camp committee that had been established immediately after the liberation was transformed into the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the British Zone, with its headquarters in the DP camp. This committee organised political congresses which called for unimpeded emigration to Palestine and the foundation of the State of Israel. Even survivors who had not already been committed Zionists before the war supported the goal of a self-determined life in Palestine.

Though the British occupying forces viewed the Jews merely as a religious community, most of the Jewish survivors themselves felt that they comprised their own nation. The Central Committee acted as the government of the Jewish DP camp and set up a police force, courts, schools, and cultural and social institutions. Many of the DPs, most of whom were young and single, started families in the camp and thus found new hope for the future. In the first two years after the liberation alone, more than one thousand Jewish couples got married in Bergen-Belsen, and well over a thousand Jewish children were born in the DP camp until it was disbanded.

A large number of DPs began leaving the camp in 1947 as their emigration opportunities improved. The State of Israel was founded in May 1948, and in early 1949 the British government lifted the last emigration restrictions. Countries like the USA and Canada also eased their immigration regulations. The Bergen-Belsen DP camp was finally dissolved in the summer of 1950.